Life Course Health Development

What is Life Course Health Development?

Life Course Health Development (commonly abbreviated as LCHD) is a key framework that underpins all of the work at the Center.

What is “Life Course?”

Scientists now understand that events and experiences in the early years can continue to influence the course of a person’s life may years later. There is a connection between the social and economic environments that a child grows up in, and almost all aspects of their future lives - whether they will finish school and go on to college, whether they will marry and have children, what their occupation will be, and the health challenges they will face along the way. In order to understand how and why health conditions develop and progress, it is essential to take a life course approach, otherwise important contributors to the difficulties that people experience later in life will be missed.

Why does Life Course Matter?

There is very strong evidence that place and circumstances of birth matter, perhaps most profoundly affecting the number of years a person is likely to live. For example, in New York City, life expectancy can differ by nearly 10 years in the 6 subway stops that separate East Harlem from Murray Hill. In Richmond, life expectancy differs by 20 years in the 5.5. miles between Westover Hills and Gilpin, and in Chicago by 16 years between the seven “L” stops that separate The Loop from Washington Park. (RWJF, 2015). Years of life lived with significant health challenges show similar patterns. While the early years are not “deterministic” nonetheless they set the stage for what comes next. For anyone wanting to intervene to improve lifelong health, it’s essential both to start with the early years, and to consider each person’s environmental interactions and lived experience as well as their genetic and biological characteristics.

What is Life Course Health Development?

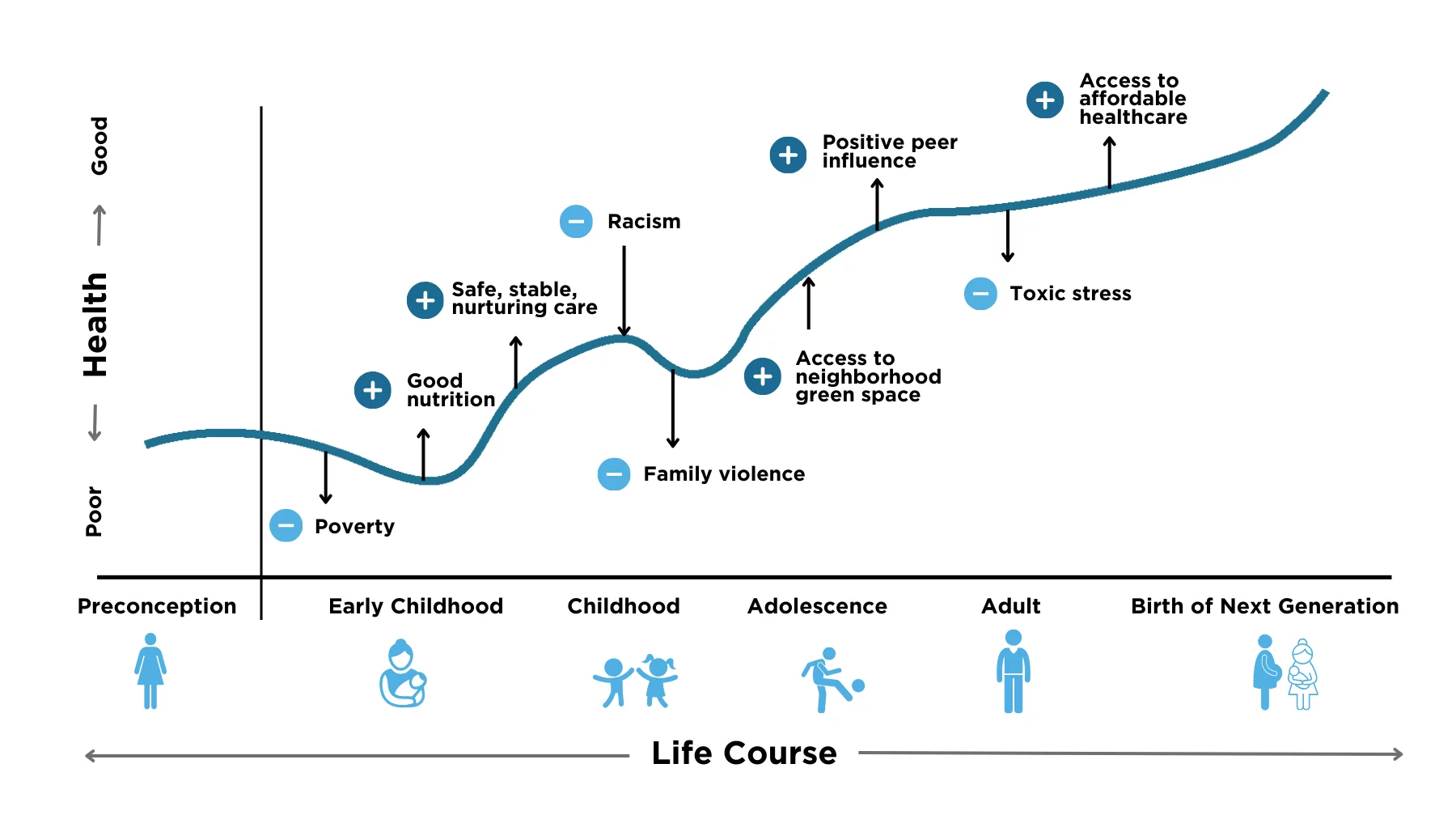

In 2002 Halfon & Hochstein created the Life Course Health Development (LCHD) framework to explain how a person’s health changes over the course of their life. Each person’s health can be represented by a trajectory, this is a path or curve that proceeds on its course over time. If you think about the way in which an arrow is aimed at a target, the path that the arrow takes can be represented by a line moving through space and time. Whether or not the arrow hits its target will depend on the skill of the archer, the quality and positioning of the bow and the arrow, the winds or obstacles the arrow might encounter on its flight, its distance from the target, and how easy the target is to see.

It is much the same with a person’s health trajectory. The course of their health will depend in part on their own genetic, biologic and physiologic make-up; their behavioral, social and economic contexts; their parents health and the quality of early caregiving; their early life experiences; the place where they grew up, played and went to school along with the safety of their neighborhoods; the people who were their extended family members and friends, and any traumas that they may have encountered over the years. If we think of “optimal health” or “well-being” as the target, anything that throws the “arrow” off course (substance use, a sudden accident), represents a risk to that person’s health. Anything that keeps the arrow on course even when there are prevailing head winds – things like stable, nurturing relationships, and reliable high quality health care, serve as “protective factors.”

Example Life Course Health Development trajectory. Positive events improve an individual's trajectory, while negative events harm the trajectory.

Yet there is one very important difference between an arrow and a person. The arrow is inert- its properties stay the same over time. A human being has the capacity for change. In fact, change and development are inevitable features of the human life course. It is this emphasis on the developmental component which makes the Halfon and Hochstein framework different from other considerations of life course theory. It places the human capacity for active development, for change, for the acquisition of health promoting behaviors, and for the ability to avoid and withstand risks centrally in the life course model. Health is not just a “passive by-product” of all that happens to a person, rather it can be actively developed over time. In other words, no matter what your current state of health, there is much that can be done to improve it.

How does Health Develop?

Each person’s health develops as an adaptive process that results from the interaction of that person’s unique characteristics with the environments that they encounter over time. Although it is very helpful to think of the way in which health develops as a curve or trajectory moving forwards through space and time, the process of health development is not linear, but complex and multi-dimensional. It is the end result of multiple interactions, or “transactions” between the person’s biological and psychological make-up, multiple aspects of their families, and communities, features of the physical environments they encounter as well as broader societal factors like health and education policy. The way the person relates to all of these other factors, and the relationships that exist within and between factors are pivotal in explaining how health develops. A person’s health pathway depends at least in part on the entire “developmental ecosystem” that surrounds them throughout their life.

How has Science Advanced our Understanding of Life Course Health Development?

In 2014, Halfon and colleagues re-visited the Life Course Health Development Framework in light of recent advances in genetics, epigenetics, and the biology of stress. Over the past two decades a considerable number of studies have reached the same conclusion- that there are plausible biological mechanisms that could account for the relationships that have been observed between external circumstances and a person’s health, especially those that occur early in life.

One of the mechanisms for which there is perhaps the most evidence is what can be understood as chronic, cumulative, or toxic “stress.” Although it is inevitable that each person will encounter some type of stress in their lives, some people have particularly stressful early childhoods e.g., children who are placed in foster care and experience unstable caregiver environments, children whose own parents may be struggling with substance use, families in extreme poverty and so on. Quite often, these early stressors are overwhelming, to the extent that they end up setting the child’s stress response on “high”- this means the body experiences many potential stimuli as “threats” leading to an internal experience of excessive or “toxic” amounts of stress. Over time, this results in excessive “wear and tear” potentially affecting every organ in the body. In fact, some scientists believe that excessive stress may be the initial “trigger” that creates the opportunity for a wide variety of diseases to take hold in a number of different body systems e.g., the development of heart disease, cancer, arthritis and so on.

In an attempt to cope with these feelings of stress, people sometimes turn to what appear at the time to be coping mechanisms e.g., use of alcohol, smoking, other substances. This only provides temporary relief from stress, and frequently lead to situations and experiences that compound the original problem. Add to this the biological impacts of these and other environmental toxins resulting in chronic inflammation, and it is not hard to see that all of these factors can combine to have a marked negative impact on a person’s health. Preventing the vicious cycles, or downward spirals in the first place is a lot more effective than waiting for serious symptoms to develop.

Life Course Health Development in Action

Life Course Translational Research Network

Learn more about LCT-RN

All Children Thrive

Learn more about ACT

Data Informed Futures

Learn more about DIF

Learn more about Life Course Health Development